Welcome back to part 2 of this series! If you have not checked out part 1 yet, please do so first, as it highlights important reconnaissance steps!

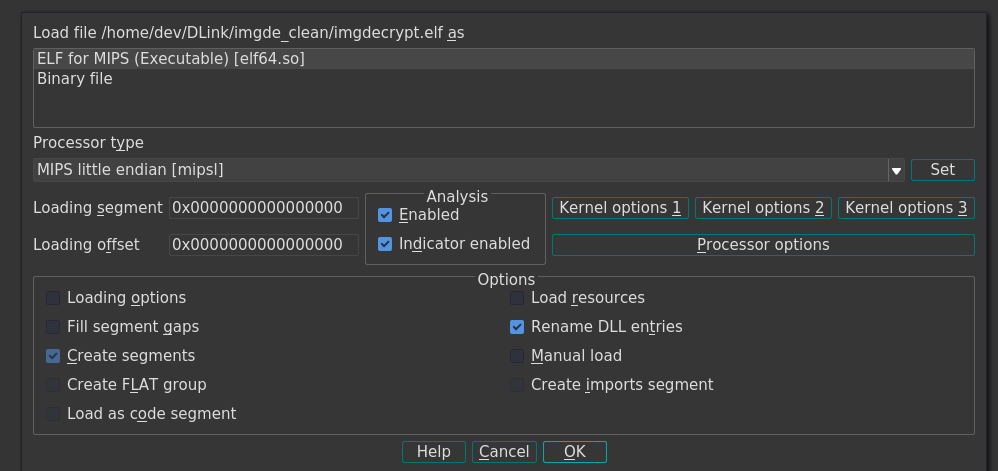

So let us dive right into the IDA adventure to get a better look at how imgdecrypt operates to secure firmware integrity of recent router models.

Right when loading the binary into IDA we're greeted with a function list which is far from bad for us. Remember? In part 1 we found out the binary is supposed to be stripped from any debug symbols, which should make it tough to debug the whole thing but in the way IDA is presenting it to us, it is rather nice:

- Overall 104 recognized functions.

- Only 16 functions that are not matched against any library function (or similar). These most likely contain the custom de-/encryption routines produced by D-Link.

- Even though the binary is called,

imgdecryptthe main entry point reveals that apparently is also has encryption capabilities!

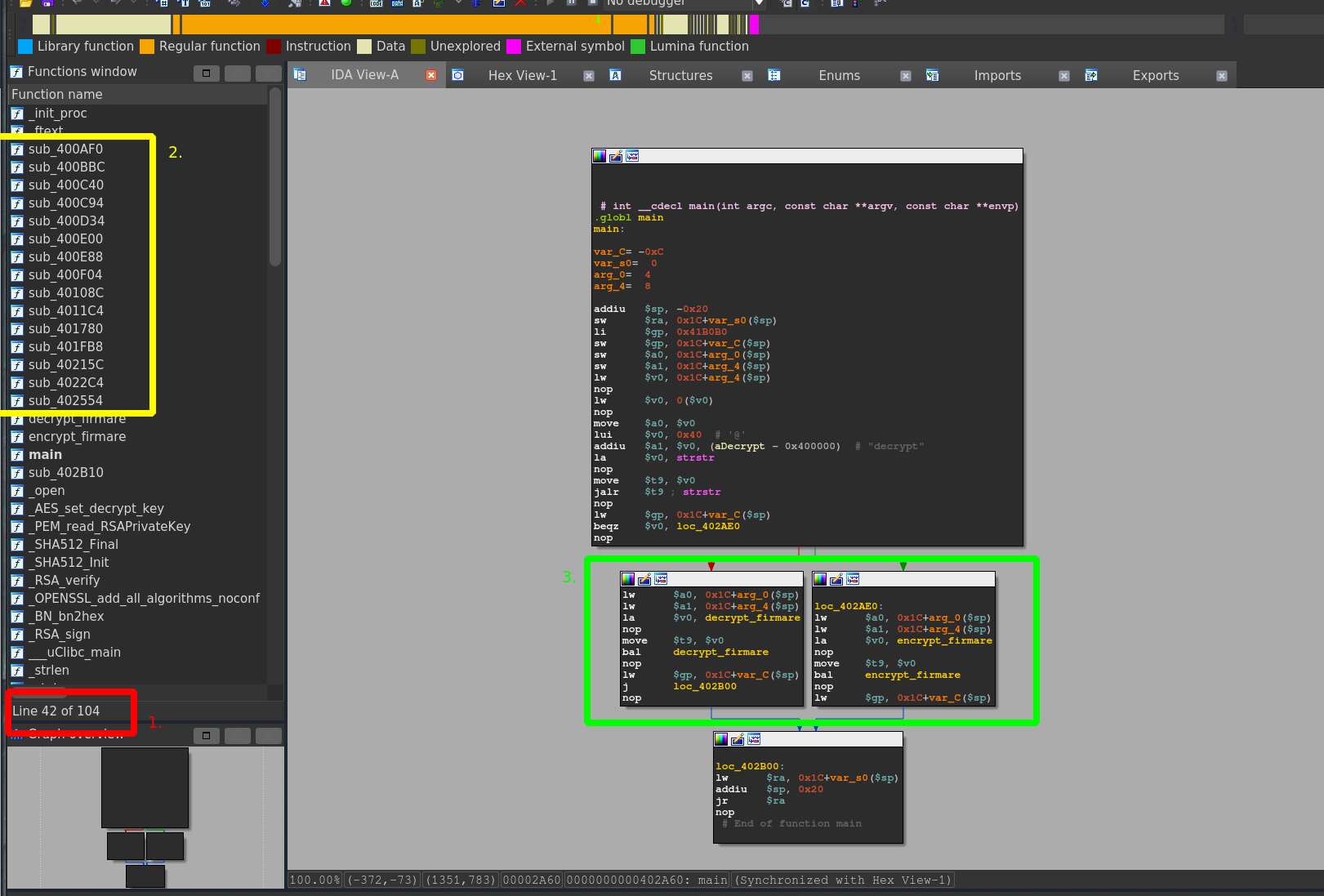

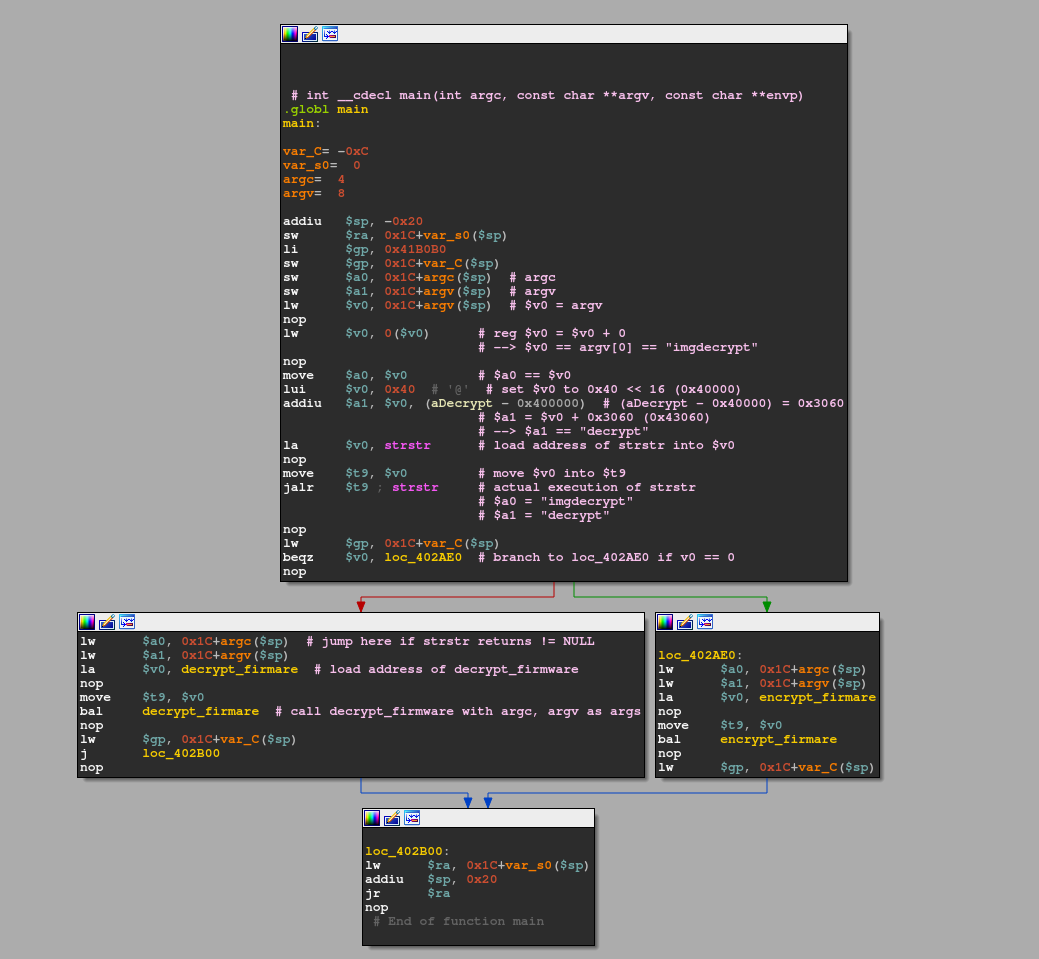

As we're interested in the decryption for now, how do we get there? Quickly annotating the main functions here leaves us with this:

The gist here is that for us to enter the decryption part of the binary, our **argv argument list has to include the substring "decrypt". If that is not the case, char *strstr(const char *haystack, const char *needle) returns, NULL as it could not find the needle ("decrypt") in the haystack (argv[0] == "imgdecrypt\0"). In case NULL is returned, the beqz $v0, loc_402AE0 instruction will evaluate to true and control flow is redirected to loc_402AE0, which is the encryption part of the binary. If you do not understand why, I heavily recommend reading part 1 of this series carefully and review the MIPS32 ABI.

Since the binary we're analyzing is called imgdecrypt and the fact that we're searching from the start of the argv space, we will always hit the correct condition to enter the decryption routine. To be able to enter the encryption routine, us renaming of the binary is necessary.

So now we know how to reach the basic block that houses decrypt_firmware. Before entering, we should take a closer look at whether the function takes any arguments and if yes, which. As you can see from the annotated version argc is loaded into $a0 and argv is loaded into $a1, which according to the MIPS32 ABI are the registers to hold the first two function arguments! With that out of the way, let's rock on!

decrypt_firmware

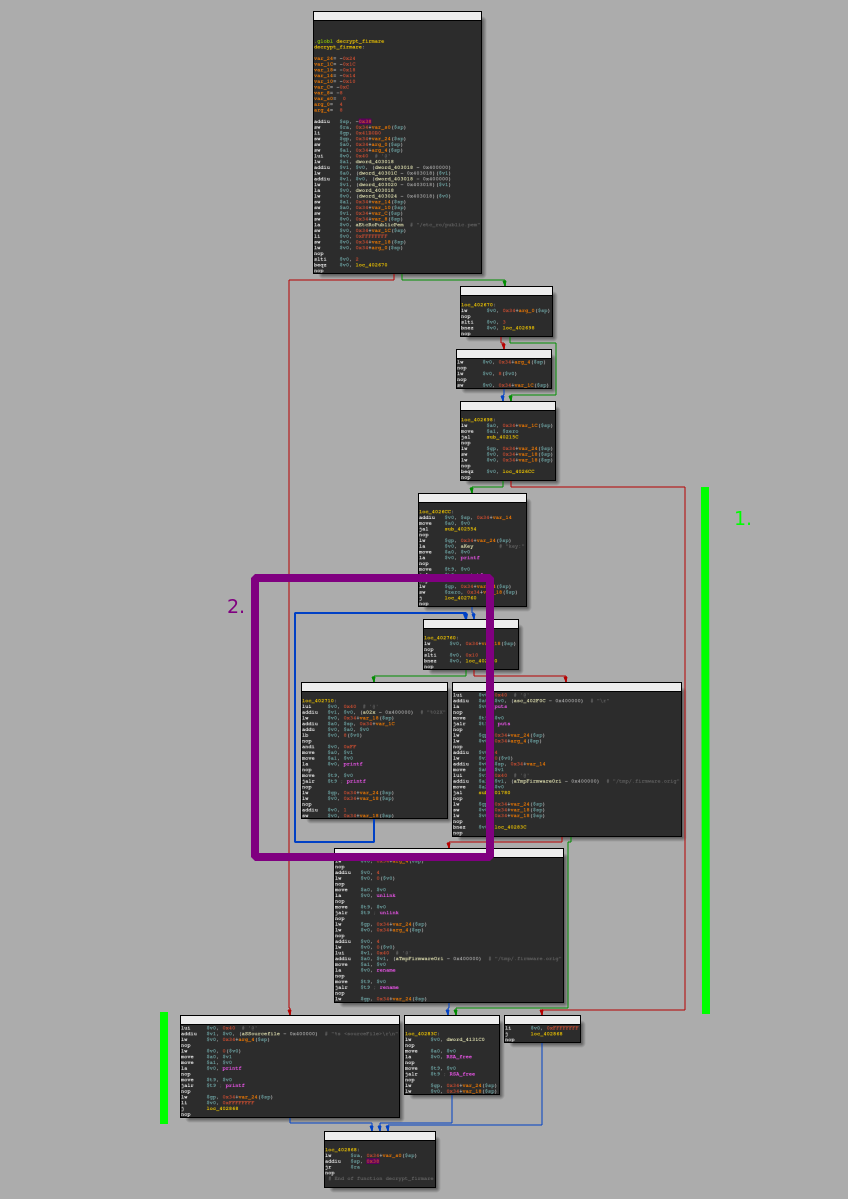

After entering the decrypt_firmware function right from how IDA groups the basic blocks in the graph view, we know two things for sure:

- There are two obvious paths we prefer not to take to continue decrypting

- There is some kind of loop in place.

Let's take a look at the first part:

I already annotated most of the interesting parts. The handful of lw and sw instructions at the beginning are setting up the stack frame and function arguments in appropriate places. The invested reader will remember the /etc_ro/public.pem from part 1. Here in the function prologue, the certificate is also set up for later usage. Besides that, there's only one interesting check at the end where argc is loaded into $v0 and then compared against 2 via slti $v0, 2, which with the next instruction of beqz $v0, loc_402670 translates to the following C-style code snippet:

if(argc < 2) {

...

} else {

goto loc_402670

}This means to properly invoke imgdecrypt we need at least one more argument (as ./imgdecrypt already means that argc is 1). This totally makes sense, as we would not gain anything from invoking this binary without supplying at least an encrypted firmware image! Let's check what the bad path we would want to avoid holds in store for us first:

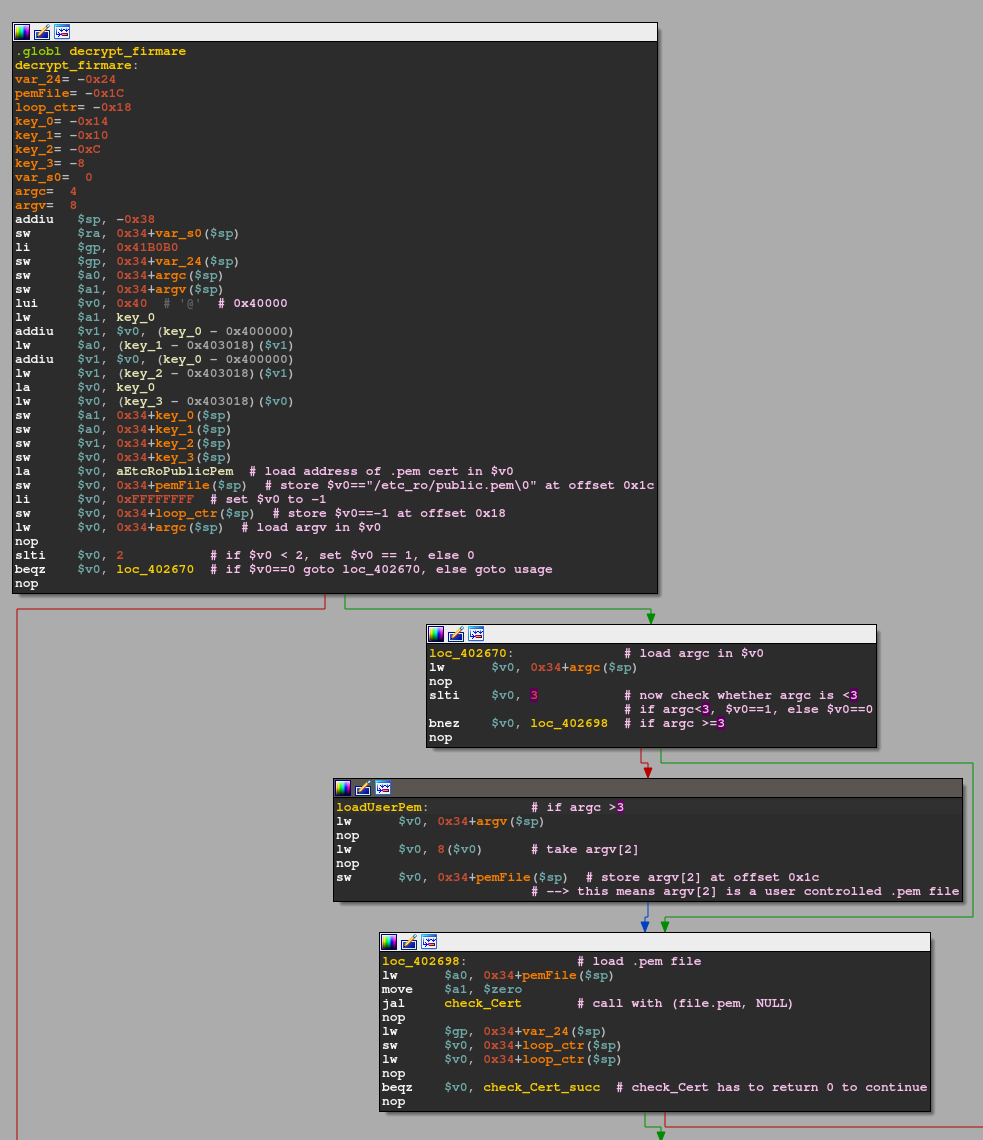

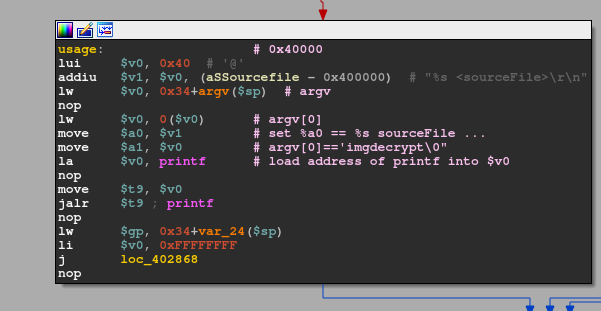

As expected, the binary takes an input file, which they denote as sourceFile. This makes sense, as the mode this binary operates in can either be decryption OR encryption. So back to the control flow we would want to follow. Once we made sure our argc is at least 2, there is another check against argc:

lw $v0, 0x34+argc($sp)

nop

slti $v0, 3

bnez $v0, loc_402698This directly translates to:

if(argc < 3) {

// $v0 == 1

goto loc_402698

} else {

// $v0 == 0

goto loadUserPem

}What I called loadUserPem allows a user to provide a custom certificate.pem upon invocation, as it is then stored at the memory location where the default /etc_ro/public.pem would have been. As this is none of our concern for now we can happily ignore this part and move on to loc_402698. There, we directly set up a function call to something I renamed to check_cert. As usual, arguments are loaded into $a0 and $a1 respectively: check_cert(pemFile, 0)

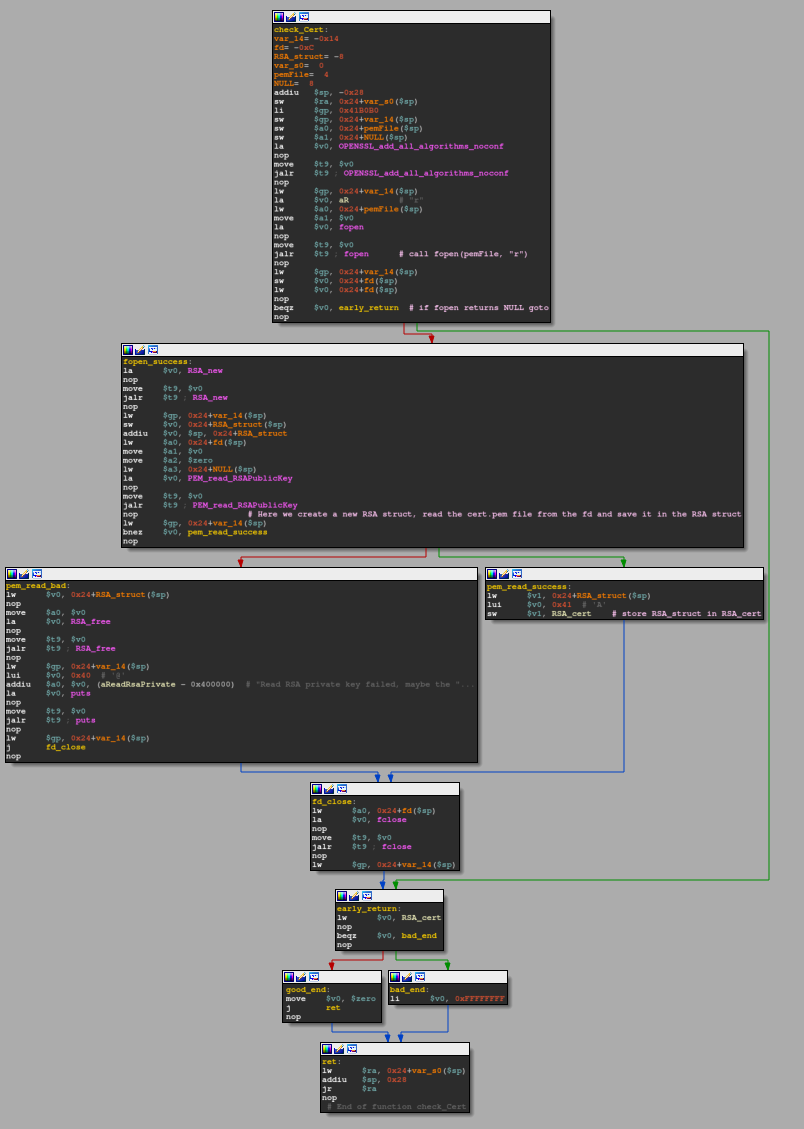

check_cert

This one is pretty straightforward as it just utilizes a bunch of library functionality.

After setting up the stack frame is done, it is being checked whether the provided certificate location is valid by doing a FILE *fopen(const char *pathname, const char *mode), which returns a NULL pointer when it fails. If that were the case the beqz $v0, early_return would evaluate to true and control flow would take the early_return path, which ultimately would end up in returning -1 from the function as lw $v0, RSA_cert; beqz $v0, bad_end would evaluate to true as the RSA_cert is not yet initialized to the point that it holds any data to pass the check against 0.

In the case, when opening the file is successful RSA *RSA_new(void) and RSA *PEM_read_RSAPublicKey(FILE fp, RSA **x, pem_password_cb *cb, void *u) are used to fill the RSA *RSA_struct. This struct has the following field members:

struct {

BIGNUM *n; // public modulus

BIGNUM *e; // public exponent

BIGNUM *d; // private exponent

BIGNUM *p; // secret prime factor

BIGNUM *q; // secret prime factor

BIGNUM *dmp1; // d mod (p-1)

BIGNUM *dmq1; // d mod (q-1)

BIGNUM *iqmp; // q^-1 mod p

// ...

}; RSA

// In public keys, the private exponent and the related secret values are NULL.

Finally, these values (aka the public key) are stored in RSA_cert in memory via the sw $v1, RSA_cert instruction. Following that is only the function tear down and once the comparison in early_return yields a value != 0 our function return value in set to 0 in the good_end basic block: move $v0, $zero.

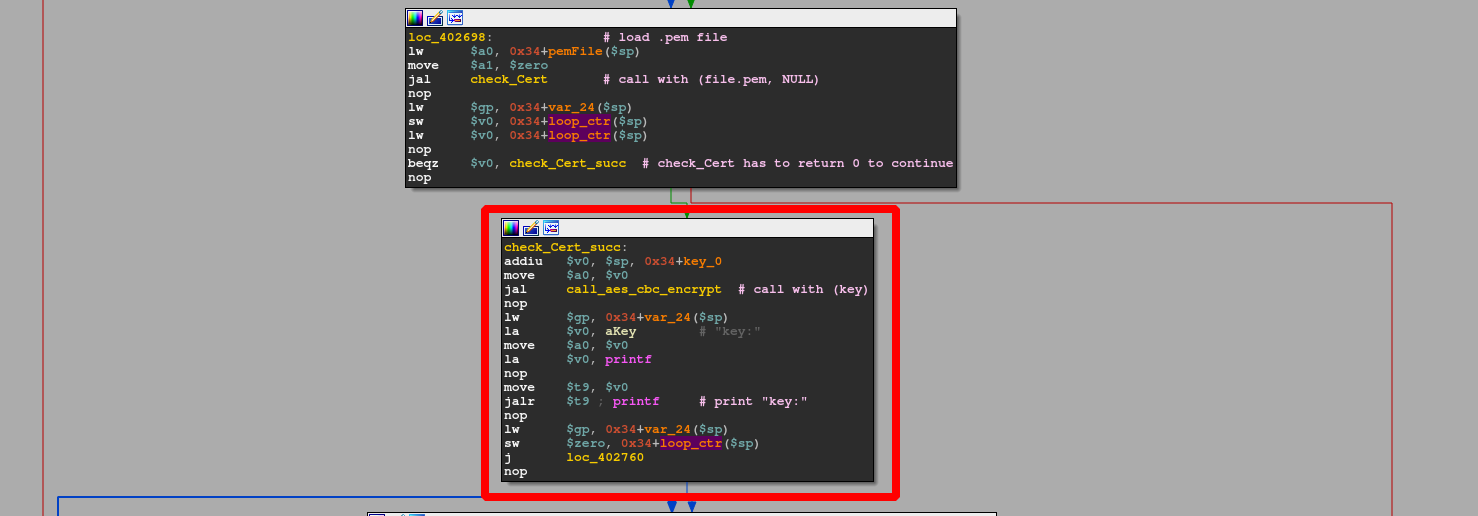

Back in decrypt_firmware the return value of check_cert is placed into memory (something I re-labeled as loop_ctr as it is reused later) and compared against 0. Only if that condition is met, control flow will continue deeper into the program to check_Cert_succ. In here, we directly redirect control flow to call_aes_cbc_encrypt() with key_0 as its first argument.

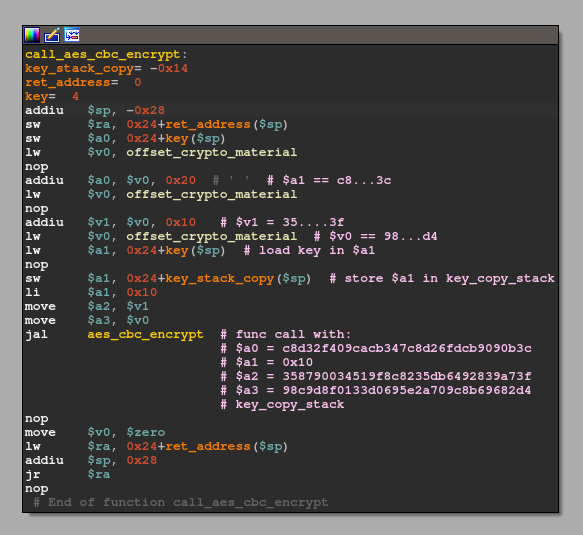

call_aes_cbc_encrypt

The function itself only acts as a wrapper, as it directly calls aes_cbc_encrypt() with 5 arguments, with the first four in registers $a0 - $a3 and the 5th one on the stack.

Four of the five arguments are hard-coded into this binary and loaded from memory via multiple: load memory base address (lw $v0, offset_crypto_material) and add an offset to it (addiu $a0, $v0, offset) operations as they are placed directly one after another:

offset_crypto_material + 0x20→C8D32F409CACB347C8D26FDCB9090B3C(in)offset_crypto_material + 0x10→358790034519F8C8235DB6492839A73F(userKey)offset_crypto_material→98C9D8F0133D0695E2A709C8B69682D4(ivec)0x10→ key length

This basically translates to a function call with the following signature: aes_cbc_encrypt(*ptrTo_C8D32F409CACB347C8D26FDCB9090B3C, 0x10, *ptrTo_358790034519F8C8235DB6492839A73F, *ptrTo_98C9D8F0133D0695E2A709C8B69682D4, *key_copy_stack). That said, I should have renamed key_copy_stack a tad better as in reality it's just a 16-byte buffer so just try to keep that in mind.

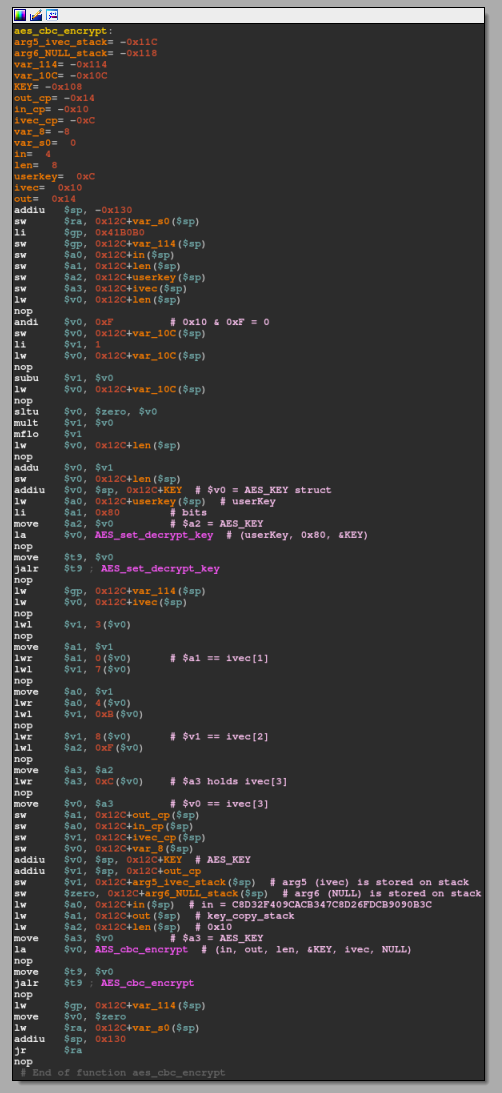

aes_cbc_encrypt

The first third of this function is the usual stack frame setup, as it needs to process 5 function arguments properly.

Additionally, an AES_KEY struct that looks as follows is defined:

#define AES_MAXNR 14

// [...]

struct aes_key_st {

#ifdef AES_LONG

unsigned long rd_key[4 *(AES_MAXNR + 1)];

#else

unsigned int rd_key[4 *(AES_MAXNR + 1)];

#endif

int rounds;

};

typedef struct aes_key_st AES_KEY;

This is needed for the first library call to AES_set_decrypt_key(const unsigned char *userKey, const int bits, AES_KEY *key), which configures key to decrypt userKey with the bits-bit key. In this particular case, the key has a size of 0x80 (128 bit == 16 byte). Finally, AES_cbc_encrypt(const uint8_t *in, uint8_t *out, size_t len, const AES_KEY *key, uint8_t *ivec, const int enc) is called. This function encrypts (or decrypts, if enc == 0) len bytes from in to out. As out was an externally supplied memory address (key_copy_stack aka the 16 byte buffer) from, call_aes_cbc_encrypt the result from AES_cbc_encrypt is directly stored in memory and not used as a dedicated return value of this function. move $v0, $zero is returned instead.

Note: For anyone wondering what these lwl and lwr do there... They indicate unaligned memory access and it looks like ivec is being accessed like an array but never used after.

Anyhow, what this function essentially does is setting the decryption key from hard-coded components. As a result, the 'generated' decryption key is the same every time. We can easily script this behavior:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from binascii import b2a_hex

inFile = bytes.fromhex('C8D32F409CACB347C8D26FDCB9090B3C')

userKey = bytes.fromhex('358790034519F8C8235DB6492839A73F')

ivec = bytes.fromhex('98C9D8F0133D0695E2A709C8B69682D4')

cipher = AES.new(userKey, AES.MODE_CBC, ivec)

b2a_hex(cipher.decrypt(inFile)).upper()

# b'C05FBF1936C99429CE2A0781F08D6AD8'Once again, we are now back in decrypt_firmware with fresh knowledge about having a static decryption key:

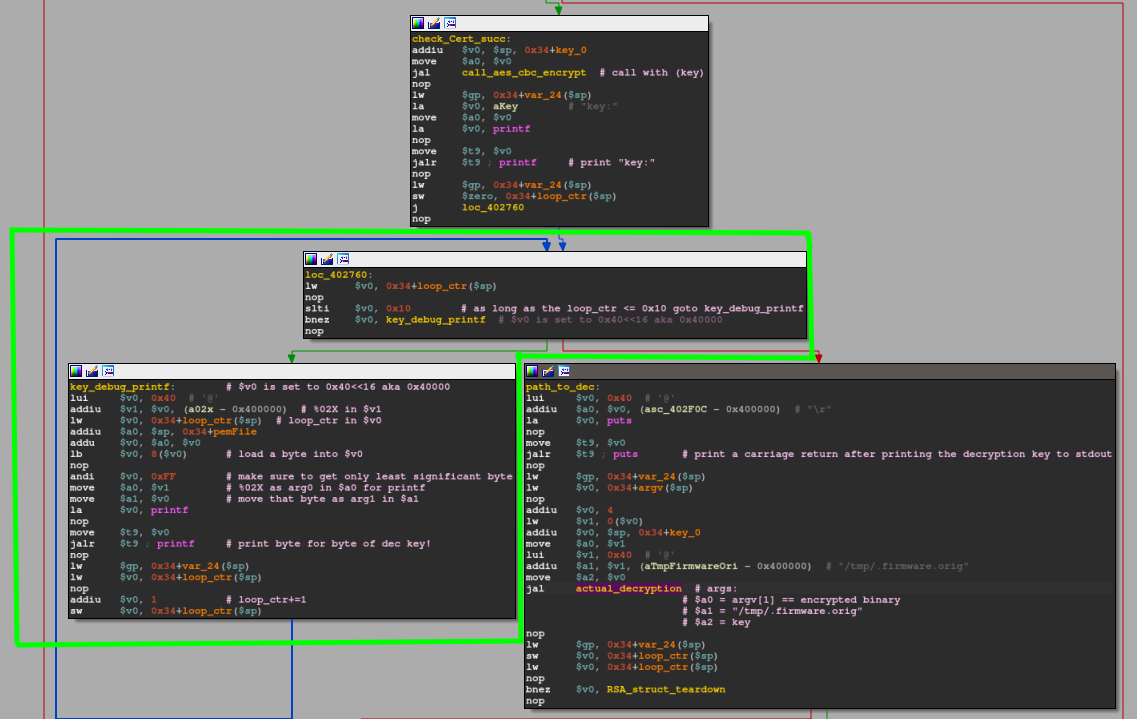

decrypt_firmware: debug print

Now it's getting funky. For whatever reason, the binary now enters a loop construct that prints out the previously calculated decryption key. The green marked basic blocks roughly translate to the following C code snippet:

int ctr = 0;

while(ctr <= 0x10 ) {

printf("%02X", *(key + ctr));

ctr += 1;

}I assume that it may be used for internal debugging so when they e.g. change the ivec they can still quickly get their hands on the new decryption key... Once printing the decryption key to stdout is over, the loop condition redirects control flow to the basic block labeled as path_to_dec where a function call to actual_decryption(argv[1], "/tmp/.firmware.orig", *key) is being prepared.

With that done, control flow and arguments are being prepared for a function call to something I labeled as actual_decryption.

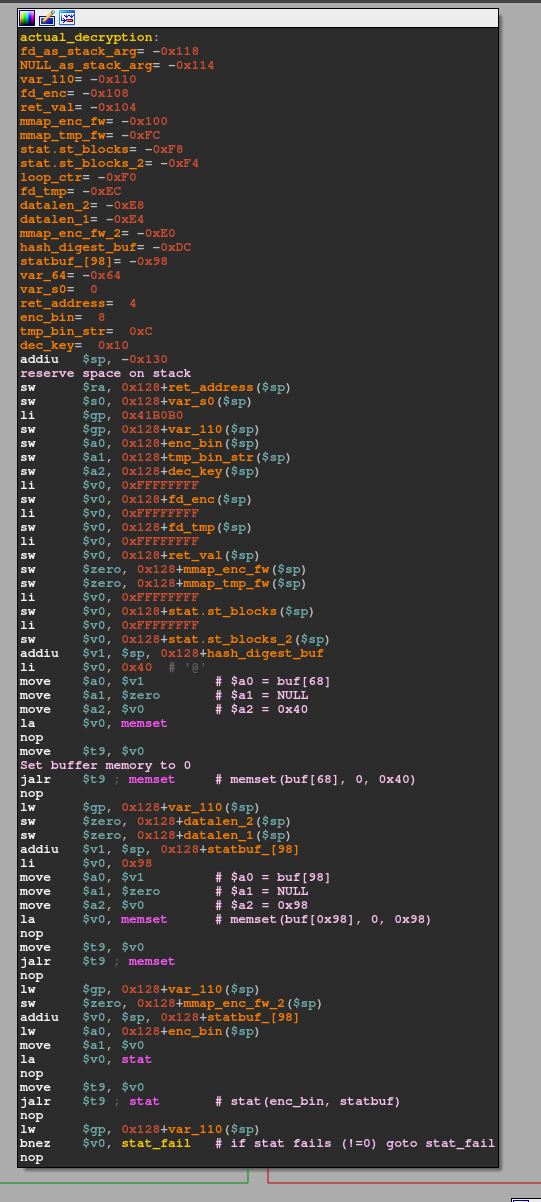

actual_decryption

This function is the meat holding this decryption scheme together.

This first part prepares two memory locations by initializing them with all 0s via void *memset(void *s, int c, size_t n). I denoted these areas as buf[68] and buf[0x98]statbuf_[98]. Directly after, the function checks if the provided sourceFile in argv[1] actually exists via a call to int stat(const char *pathname, struct stat *statbuf). The result of that one is stored within a stat struct that looks as follows:

struct stat {

dev_t st_dev; /* ID of device containing file */

ino_t st_ino; /* Inode number */

mode_t st_mode; /* File type and mode */

nlink_t st_nlink; /* Number of hard links */

uid_t st_uid; /* User ID of owner */

gid_t st_gid; /* Group ID of owner */

dev_t st_rdev; /* Device ID (if special file) */

off_t st_size; /* Total size, in bytes */

blksize_t st_blksize; /* Block size for filesystem I/O */

blkcnt_t st_blocks; /* Number of 512B blocks allocated */

/* Since Linux 2.6, the kernel supports nanosecond

precision for the following timestamp fields.

For the details before Linux 2.6, see NOTES. */

struct timespec st_atim; /* Time of last access */

struct timespec st_mtim; /* Time of last modification */

struct timespec st_ctim; /* Time of last status change */

#define st_atime st_atim.tv_sec /* Backward compatibility */

#define st_mtime st_mtim.tv_sec

#define st_ctime st_ctim.tv_sec

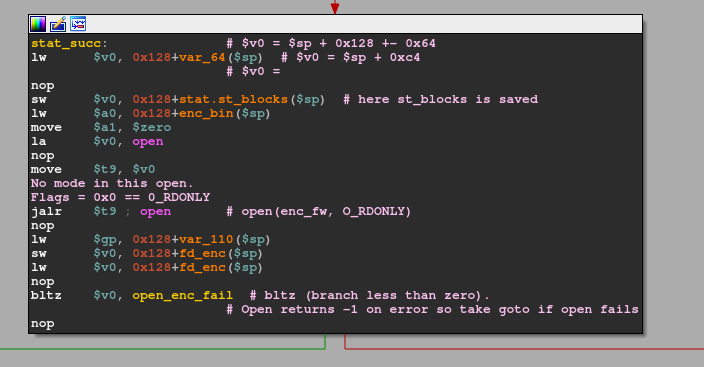

};On success (meaning pathname exists) stat returns 0. So on failure that bnez $v0, stat_fail would follow the branch to stat_fail. So, we want to make sure $v0 is 0 to continue normally. The desired control flow continues here:

Here, besides some local variable saving the sourceFile is opened in read-only mode, indicated by the 0x0 flag provided to the open(const char *pathname, int flags). The result/returned file descriptor of that call is saved to 0x128+fd_enc. Similar to the stat routine before, it is being checked whether open(sourceFile, O_RDONLY) is successful as indicated by bltz $v0, open_enc_fail. The branch to open_enc_fail is only taken if $v0 < 0, which is only the case when the call to open fails (-1 is returned in this case). So assuming the open call succeeds, we get to the next part with $v0 holding the open file descriptor:

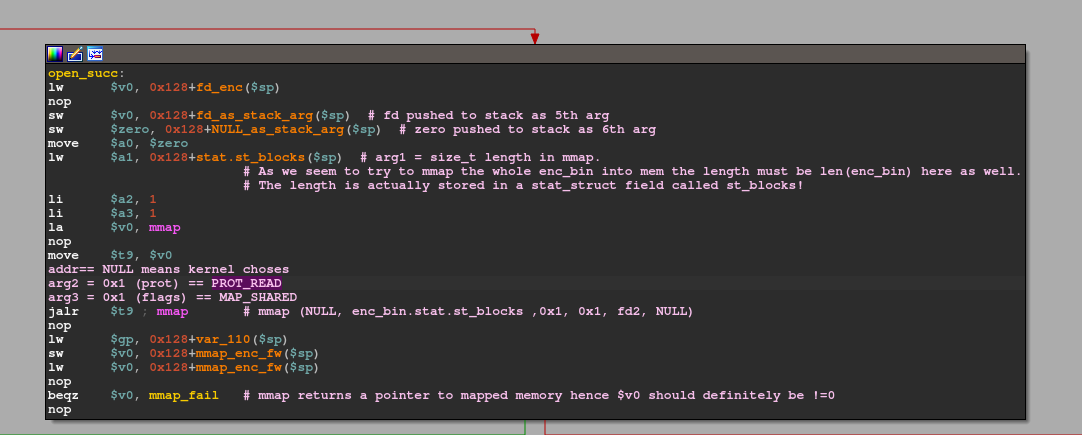

This basically attempts to use void mmap(void addr, size_t length, int prot, int flags, int fd, off_t offset) to map the just opened file into a kernel chosen memory region ( indicated by *addr == 0) that is shared but read-only.

Such flags can easily be extracted from the header files on any system as follows:

> egrep -i '(PROT_|MAP_)' /usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/bits/mman-linux.h

implementation does not necessarily support PROT_EXEC or PROT_WRITE

without PROT_READ. The only guarantees are that no writing will be

allowed without PROT_WRITE and no access will be allowed for PROT_NONE. */

#define PROT_READ 0x1 /* Page can be read. */

#define PROT_WRITE 0x2 /* Page can be written. */

#define PROT_EXEC 0x4 /* Page can be executed. */

#define PROT_NONE 0x0 /* Page can not be accessed. */

#define PROT_GROWSDOWN 0x01000000 /* Extend change to start of

#define PROT_GROWSUP 0x02000000 /* Extend change to start of

#define MAP_SHARED 0x01 /* Share changes. */

#define MAP_PRIVATE 0x02 /* Changes are private. */

# define MAP_SHARED_VALIDATE 0x03 /* Share changes and validate

# define MAP_TYPE 0x0f /* Mask for type of mapping. */

#define MAP_FIXED 0x10 /* Interpret addr exactly. */

# define MAP_FILE 0

# ifdef __MAP_ANONYMOUS

# define MAP_ANONYMOUS __MAP_ANONYMOUS /* Don't use a file. */

# define MAP_ANONYMOUS 0x20 /* Don't use a file. */

# define MAP_ANON MAP_ANONYMOUS

/* When MAP_HUGETLB is set bits [26:31] encode the log2 of the huge page size. */

# define MAP_HUGE_SHIFT 26

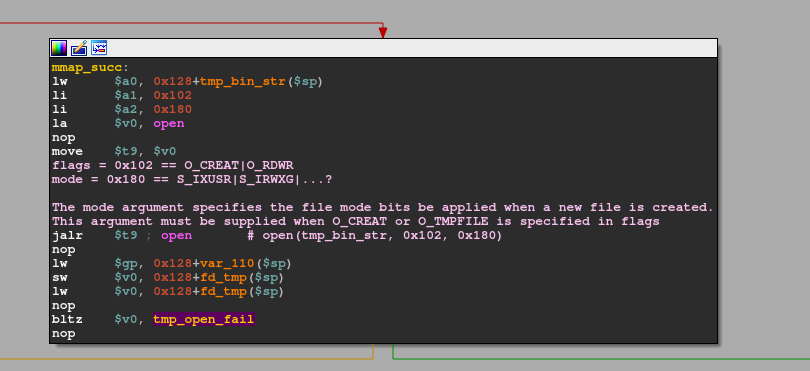

# define MAP_HUGE_MASK 0x3fIn this case, the stat call from earlier comes in handy once again as it is not just used to verify whether the provided file in argv[1] actually exists, but the statStruct also contains the struct member st_blocks which can be used to fill in the required size_t length argument in mmap! The return value of mmap is stored in 0x128+mmap_enc_fw($sp). Once again, we have another 'if' condition type branching to check whether the memory mapping was successful. On success, mmap returns a pointer to the mapped area and branching on beqz $v0, mmap_fail does not take places since $v0 holds a value != 0. Following this is a final call to open:

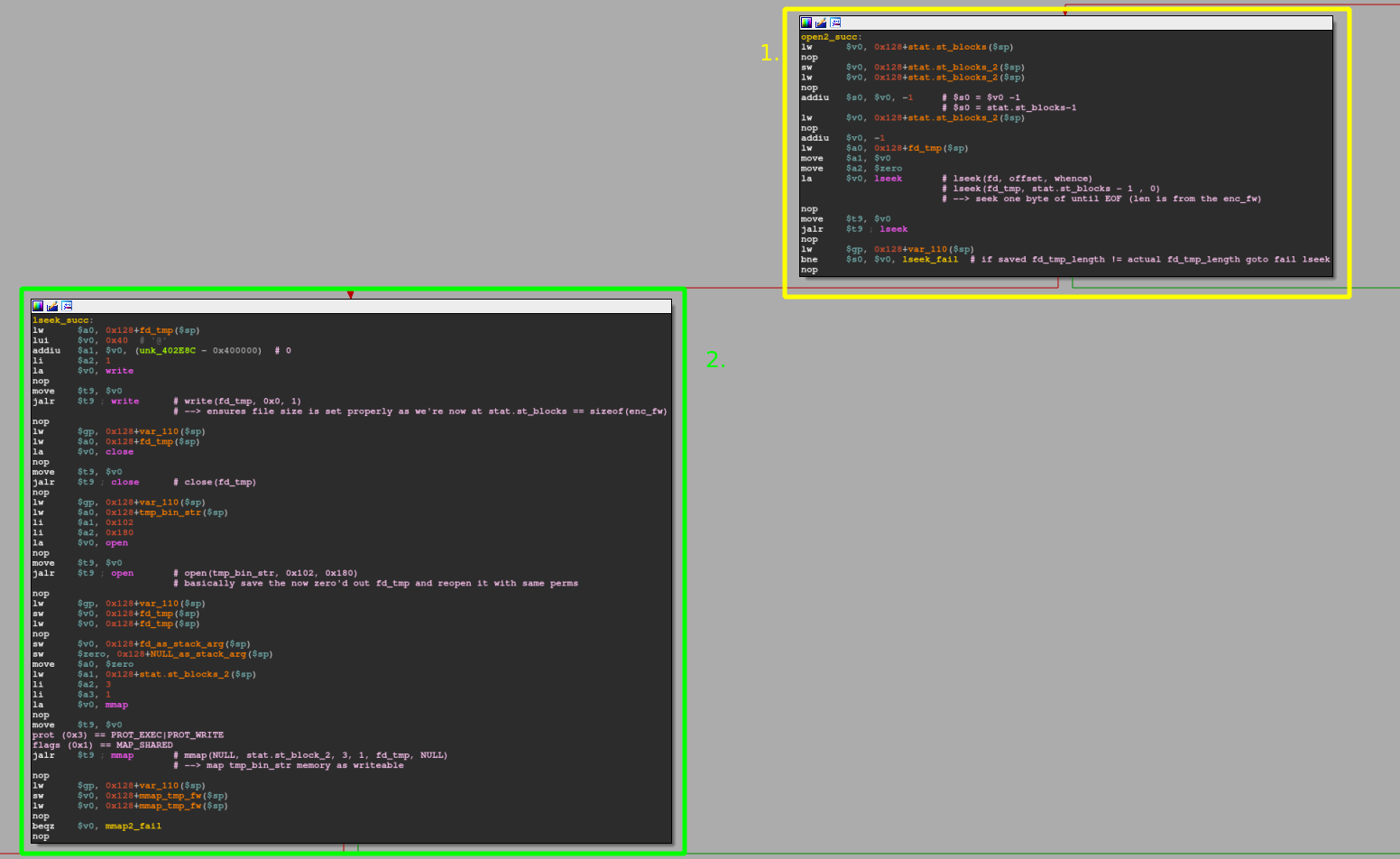

This only tries to open the predefined path ("/tmp/.firmware.orig") as read+write with the new file descriptor being saved in 0x128+fd_tmp($sp). As usual, if the open fails, branch to the fail portion of this function. On success, this leads us to the final preparation step:

- Here we're preparing to set the correct size of the freshly opened file in the /tmp/ location by first seeking to offset

stat.st_blocks -1by invokinglseek(fd_tmp, stat.st_blocks -1). - When the lseek succeeds, we write a single 0 to the file at said offset. This allows us to easily and quickly create an "empty" file without having to write N bytes in total (where N== desired file size in bytes). Finally, we close, re-open and re-map the file with new permissions.

Side note: We do not need all these if-condition like checks realized through beqz, bnez, ... as we already know for sure the file exists by now...

Intermediate summary

So far, we didn't manage to dig any deeper into the decryption routine because of all this file preparation stuff. Luckily, I can tease you as much as that, we're done with that now. As we have already roughly met the 15-minute mark for the reading time, I'll stop here. The very soon upcoming 2nd part of this write-up will solely focus on the cryptographic aspects of the scheme D-Link utilizes.

If, for any reason, you weren't able to follow properly until here, you can find the whole source code up to this point below. You should be able to compile it with clang/gcc via clang/gcc -o imgdecrypt imgdecrypt.c -L/usr/local/lib -lssl -lcrypto -s on any recent Debian based system. This in particular comes in handy if you're new to MIPS and would much more prefer looking at x86 disassembly. The x86 reversing experience should be close to the original MIPS one, only with some minor deviations due to platform differences.

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <openssl/aes.h>

#include <openssl/pem.h>

#include <openssl/rsa.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

static RSA *grsa_struct = NULL;

static unsigned char iv[] = {0x98, 0xC9, 0xD8, 0xF0, 0x13, 0x3D, 0x06, 0x95,

0xE2, 0xA7, 0x09, 0xC8, 0xB6, 0x96, 0x82, 0xD4};

static unsigned char aes_in[] = {0xC8, 0xD3, 0x2F, 0x40, 0x9C, 0xAC,

0xB3, 0x47, 0xC8, 0xD2, 0x6F, 0xDC,

0xB9, 0x09, 0x0B, 0x3C};

static unsigned char aes_key[] = {0x35, 0x87, 0x90, 0x03, 0x45, 0x19,

0xF8, 0xC8, 0x23, 0x5D, 0xB6, 0x49,

0x28, 0x39, 0xA7, 0x3F};

unsigned char out[] = {0x30, 0x31, 0x32, 0x33, 0x34, 0x35, 0x36, 0x37,

0x38, 0x39, 0x41, 0x42, 0x43, 0x44, 0x45, 0x46};

int check_cert(char *pem, void *n) {

OPENSSL_add_all_algorithms_noconf();

FILE *pem_fd = fopen(pem, "r");

if (pem_fd != NULL) {

RSA *lrsa_struct[2];

*lrsa_struct = RSA_new();

if (!PEM_read_RSAPublicKey(pem_fd, lrsa_struct, NULL, n)) {

RSA_free(*lrsa_struct);

puts("Read RSA private key failed, maybe the password is incorrect.");

} else {

grsa_struct = *lrsa_struct;

}

fclose(pem_fd);

}

if (grsa_struct != NULL) {

return 0;

} else {

return -1;

}

}

int aes_cbc_encrypt(size_t length, unsigned char *key) {

AES_KEY dec_key;

AES_set_decrypt_key(aes_key, sizeof(aes_key) * 8, &dec_key);

AES_cbc_encrypt(aes_in, key, length, &dec_key, iv, AES_DECRYPT);

return 0;

}

int call_aes_cbc_encrypt(unsigned char *key) {

aes_cbc_encrypt(0x10, key);

return 0;

}

int actual_decryption(char *sourceFile, char *tmpDecPath, unsigned char *key) {

int ret_val = -1;

size_t st_blocks = -1;

struct stat statStruct;

int fd = -1;

int fd2 = -1;

void *ROM = 0;

int *RWMEM;

off_t seek_off;

unsigned char buf_68[68];

int st;

memset(&buf_68, 0, 0x40);

memset(&statStruct, 0, 0x90);

st = stat(sourceFile, &statStruct);

if (st == 0) {

fd = open(sourceFile, O_RDONLY);

st_blocks = statStruct.st_blocks;

if (((-1 < fd) &&

(ROM = mmap(0, statStruct.st_blocks, 1, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0),

ROM != 0)) &&

(fd2 = open(tmpDecPath, O_RDWR | O_NOCTTY, 0x180), -1 < fd2)) {

seek_off = lseek(fd2, statStruct.st_blocks - 1, 0);

if (seek_off == statStruct.st_blocks - 1) {

write(fd2, 0, 1);

close(fd2);

fd2 = open(tmpDecPath, O_RDWR | O_NOCTTY, 0x180);

RWMEM = mmap(0, statStruct.st_blocks, PROT_EXEC | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_SHARED, fd2, 0);

if (RWMEM != NULL) {

ret_val = 0;

}

}

}

}

puts("EOF part 2.1!\n");

return ret_val;

}

int decrypt_firmware(int argc, char **argv) {

int ret;

unsigned char key[] = {0x30, 0x31, 0x32, 0x33, 0x34, 0x35, 0x36, 0x37,

0x38, 0x39, 0x41, 0x42, 0x43, 0x44, 0x45, 0x46};

char *ppem = "/tmp/public.pem";

int loopCtr = 0;

if (argc < 2) {

printf("%s <sourceFile>\r\n", argv[0]);

ret = -1;

} else {

if (2 < argc) {

ppem = (char *)argv[2];

}

int cc = check_cert(ppem, (void *)0);

if (cc == 0) {

call_aes_cbc_encrypt((unsigned char *)&key);

printf("key: ");

while (loopCtr < 0x10) {

printf("%02X", *(key + loopCtr) & 0xff);

loopCtr += 1;

}

puts("\r");

ret = actual_decryption((char *)argv[1], "/tmp/.firmware.orig",

(unsigned char *)&key);

if (ret == 0) {

unlink(argv[1]);

rename("/tmp/.firmware.orig", argv[1]);

}

RSA_free(grsa_struct);

} else {

ret = -1;

}

}

return ret;

}

int encrypt_firmware(int argc, char **argv) { return 0; }

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int ret;

char *str_f = strstr(*argv, "decrypt");

if (str_f != NULL) {

ret = decrypt_firmware(argc, argv);

} else {

ret = encrypt_firmware(argc, argv);

}

return ret;

}> ./imgdecrypt

./imgdecrypt <sourceFile>

> ./imgdecrypt testFile

key: C05FBF1936C99429CE2A0781F08D6AD8

EOF part 2.1!The next part 2.2 will be online shortly and linked here as soon as it is available.

Thanks for reading and if you have any questions or remarks feel free to hit me up :)!